Every month, Forest2Market publishes updated forecasting products designed specifically for participants in the forest value chain. The Economic Outlook is a macroeconomic indicator forecast that supplies critical information, context and insight about general economic trends and direction, and the 4Cast supports regional operational decision making for those who buy and sell timber. With an understanding of economic indicators, future stumpage prices and insight into buying and selling windows (periods in which buyers or sellers hold relative market advantage), subscribers are better able to time sales or purchases, negotiate prices, manage workloads and control inventory levels. The following commentary is just a sampling from the most recent Economic Outlook for January, 2019.

Citing a “strengthening” labor market and economic activity that has been “rising at a strong rate,” the Federal Reserve’s Open Market Committee (FOMC) announced a 0.25PP hike to the federal funds rate (FFR) at the conclusion of its December 18-19 meeting. Materials accompanying the press conference suggest two rate hikes in 2019, a decrease from the September forecast that is consistent with gradually waning growth expectations.

Many analysts have questioned the logic of raising rates, arguing the Fed is “triple tightening” the global economy into potential recession. I.e., the FOMC is pursuing monetary policy that affects the economy in three ways.

The most obvious and direct way is via interest rates. Savers, and particularly retirees, have been decimated by the past decade’s paltry returns on investment. We have long felt interest rates should not have been cut as drastically or suppressed for as long as they were. Although savers will benefit—and discipline on investment quality will tighten—if rates continue rising, it follows that borrowing costs will correspondingly increase for indebted consumers, businesses and governments.

The second way is an offshoot of the first: Comparatively higher US interest rates attract capital flows into the United States from lower-interest economies, resulting in a stronger dollar. In so doing, wrote analyst Ira Iosebashvili, “a stronger US dollar can dent emerging markets because it pushes down the value of their currencies, makes dollar-denominated debt more expensive to repay and increases the cost of commodities and other goods priced in dollars.” Of course, as capital flows into Treasuries and other bonds, their prices are bid up and yields tamped down; hence, interest rates and downstream impacts are likely to fluctuate over the short-to-medium terms.

The third way relates to the Fed’s balance-sheet unwind. The money supply effectively shrinks as the Fed allows the US Treasury bonds and mortgage-backed securities, which it bought during the Great Recession, to expire. At the present $50 billion/month rate of balance-sheet runoff, this aspect of quantitative tightening is the equivalent of two to four rate hikes per year over and above the explicit rate hikes. By the end of 2019 the Fed will tighten monetary conditions by the equivalent of a 2.2PP rate hike.

So, we return to the question of why the FOMC is pursuing tighter monetary policy despite the associated risks. Based upon a variety of sources, we conclude the FOMC is caught in an unenviable choice between:

- Keeping rates low to prevent tipping overleveraged debtors into insolvency; and

- Raising rates in an attempt to avoid (or at least postpone) a crisis in underfunded pension programs, and to create room to cut rates when the next recession arrives.

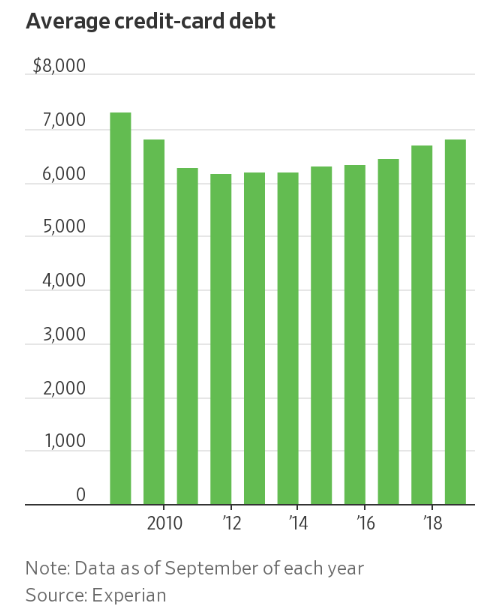

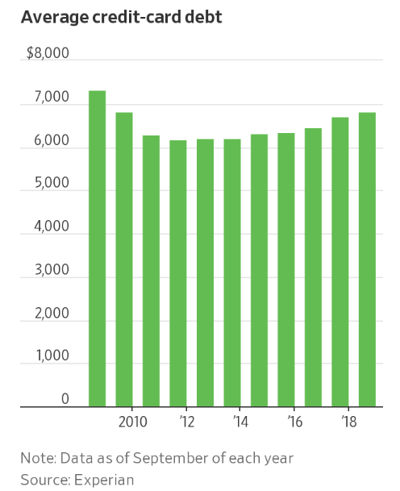

The risk raised by the first choice is not merely theoretical. Consumer debt is on pace to top $4 trillion in 2019. The good news is thus far defaults remain low, but higher interest rates could rapidly change that situation. For fiscal year 2018, US debt fell just shy of $22 trillion, or approximately 105% of US annual GDP. Nor does the debt parade stop at the US border; worldwide debt was 225% of global GDP in 2017, or $86,000 per capita. The prospect of higher interest rates under such conditions does not bode well for either US or global economic growth, and underscores the risks the Fed is navigating while trying to “normalize” the interest rate environment.

If, as we expect, the FOMC ignores pressure to pause for six months, and instead raises rates twice in 2019, the hikes will most likely coincide with the March and June meetings (ultimately, raising the prime rate to 6.0%)—a case of getting the hikes “while the getting is good.” Fed watchers seem to agree with this assessment, as recently they have at times assigned higher probabilities of a rate cut rather than an increase by December 2019.