3 min read

April Labor Market Data Confirms Historic Job Losses, Challenges Ahead

Forest2Market

:

May 28, 2020

Every month, Forest2Market publishes updated forecasting products designed specifically for participants in the forest value chain. The Economic Outlook is a macroeconomic indicator forecast that supplies critical information, context and insight about general economic trends and direction, and the 4Cast supports regional operational decision making for those who buy and sell timber.

With an understanding of economic indicators, future stumpage prices and insight into buying and selling windows (periods in which buyers or sellers hold relative market advantage), subscribers are better able to time sales or purchases, negotiate prices, manage workloads and control inventory levels amid highly uncertain markets. The following commentary is just a sampling from the most recent Economic Outlook for May 2020.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics’ (BLS) establishment survey showed that non-farm payroll employment crashed by a worst-ever 20.5 million jobs in April (-21.25 million expected); the BLS subsequently revised its job-loss estimate to -20.537 million. That was in addition to February and March employment changes that were revised down by a combined 214,000. Meanwhile, the unemployment rate (based upon the BLS’s household survey) leapt (+10.3PP, the largest post-WWII MoM rate increase) to 14.7% under a combination of a shrinking labor force (-6.432 million) and a plummeting number of employed persons (-22.369 million).

The number of employment-age persons not in the labor force jumped (+6.57 million) to 103.4 million. Because the civilian labor force shrank by the above-mentioned 6.4 million (since lockdowns made looking for work much more difficult, and thus many workers were considered not in the labor force), the labor force participation rate fell (-2.5PP) to 60.2%.

Goods-producing industries lost 2.355 million jobs, while service-providing employment (-18.145 million jobs) again bore the brunt of the drop—especially leisure and hospitality (-7.653 million), retail trade (-2.107 million), health care and social assistance (-2.087 million), and administrative and support services (-1.523 million). Manufacturing contracted by 1.330 million jobs. That result is consistent with ISM’s manufacturing employment sub-index, which fell into deep contraction in April. Wood Products employment retreated by 27,900 (ISM decreased); Paper and Paper Products: -8,200 (ISM unchanged); Construction: -975,000 (ISM decreased).

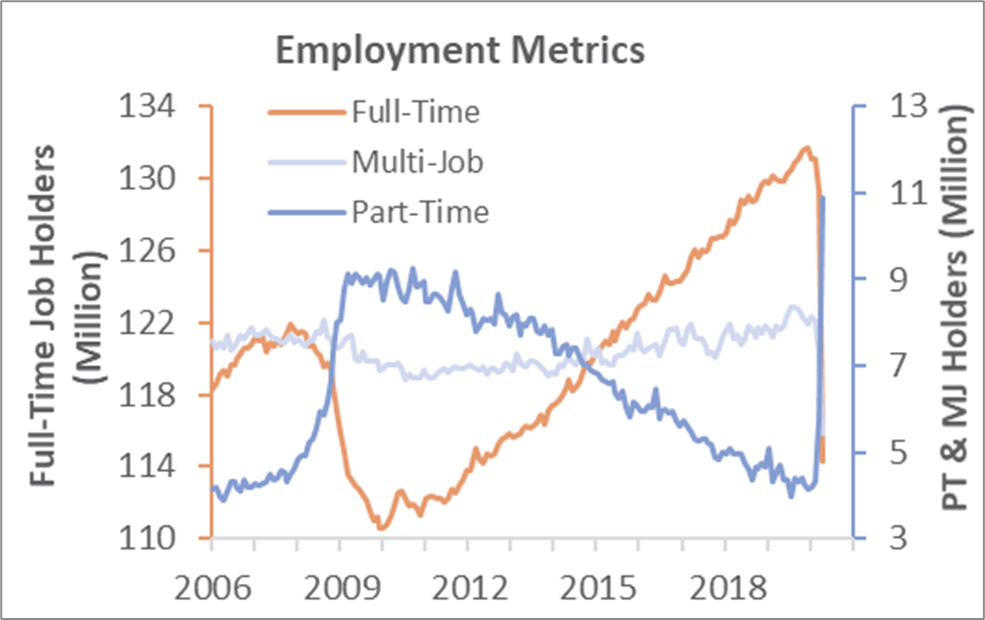

Full-time jobs tumbled (-15.0 million), to 114.3 million. Workers employed part time for economic reasons (shown in the graph above)—e.g., slack work or business conditions, or could find only part-time work—jumped by 5.1 million; many in this category had been full-time workers. Those working part time for non-economic reasons slumped by 8.2 million, while multiple-job holders fell by 1.8 million.

Average hourly earnings of all private employees rose by $1.34 to $30.01, resulting in a 7.9% year-over-year increase. In data back to 2006, average hourly earnings had never risen by more than $0.15 MoM; April’s reading suggests that employees still working are those toward the upper end of their respective wage ranges. It also buttresses Fed Chair Powell’s observation that 40% of US households earning less than $40,000 a year lost their jobs in March. Since the average workweek for all employees on private nonfarm payrolls expanded (+0.1 hour) to 34.2 hours, average weekly earnings increased by $48.69, to $1,026.34 (+7.3% YoY).

Per the BLS, “in the establishment survey, workers who are paid by their employer for all or any part of the pay period including the 12th of the month are counted as employed, even if they were not actually at their jobs. Workers who are temporarily or permanently absent from their jobs and are not being paid are not counted as employed, even if they are continuing to receive benefits.” Because many more individuals have filed for unemployment during the latter part of April, May’s employment numbers will also be dismal.

A variety of both fiscal (government spending) and monetary (Federal Reserve) assistance programs have been initiated to blunt the impacts of massive job losses resulting from government-initiated and -enforced lockdowns; most programs have been aimed at supporting employees and employers. Despite anecdotal complaints regarding the programs’ efficacy, early analysis suggests the programs may be achieving at least some desired results.

Nonetheless, total fiscal outlays so far (aid either given directly or through loans) is $2.8 trillion—over three times the size of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, the Great Recession’s keystone stimulus program.