4 min read

Biased Coverage of Rainforests Impacts Brazil’s Primary Forest Industry

Marcelo Schmid

:

August 28, 2019

Marcelo Schmid

:

August 28, 2019

The executive branch of the Brazilian government recently questioned the official data citing an increase in deforestation of the Amazon rainforest, which was published by the National Institute for Space Research (INPE). Importantly, this data was updated after the current administration expressed some degree of skepticism regarding a number of high-profile environmental issues. The public row has resulted in the resignation of the president of the Institute, and the government's position has prompted (or, resurrected) an intense discussion about public policies regarding territorial and environmental management of the Amazon region.

Heavily leveraged by the Brazilian media, the debate has extended well beyond national borders and has been treated as a toxic “bombshell” by some international news agencies, who have even questioned Brazil’s ability to effectively manage and conserve its rainforests. There is a legitimate debate regarding the reliability and methodology of deforestation monitoring and data collection, as well as how that data is aggregated, interpreted and disseminated. However, the debate has resulted in a great deal of confusion and distortions that are then applied, oftentimes erroneously, to the larger Brazilian forest sector.

Regardless of the accuracy of the INPE data, it is imperative to clearly delineate between commercial wood production and related forest industry activities in Brazil versus what sensational media reports claim is occurring in the Amazon region. Unfortunately, linking Amazonian deforestation to general “logging” is both common and misleading because:

- What is often referred to as a “logger” is usually a timber producer who is connected to a forest-based industrial enterprise. Since the forest is a timber producer’s source of supply and income, his interest lies not the destruction of the environment, but in the preservation and growth of forest raw materials.

- The major driver of deforestation in the Amazon rainforest over the past 20 years, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), has been the conversion of forestland to pastureland, not harvesting for timber.

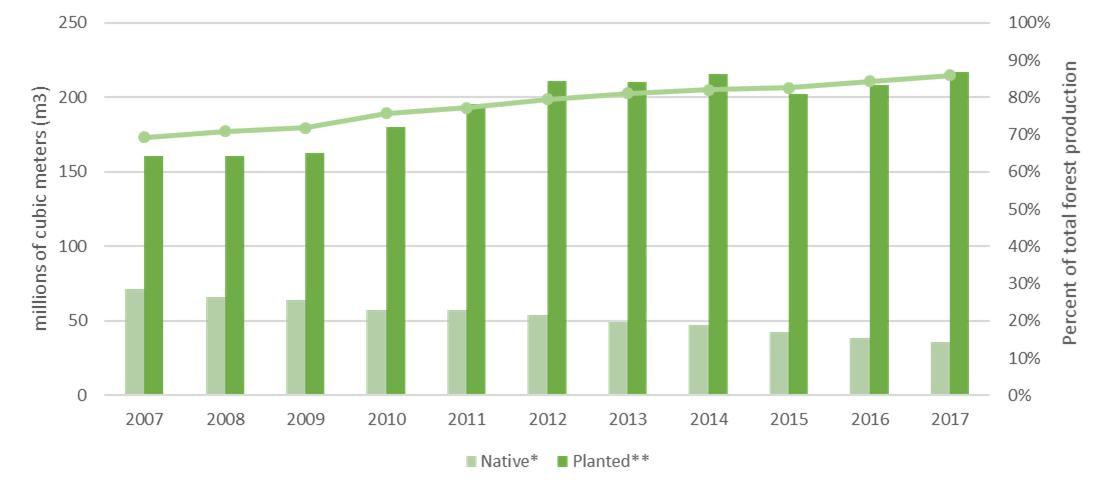

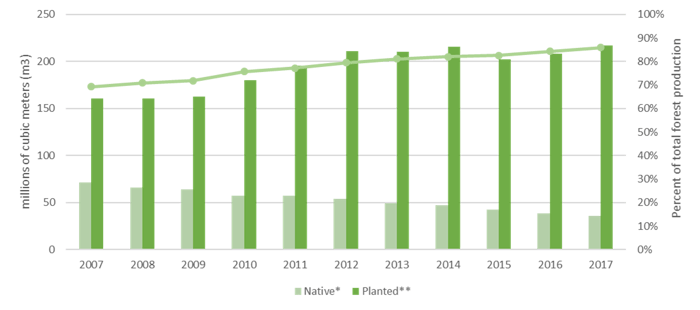

- In terms of total forest production in Brazil, the share of wood derived from the Amazon is very small. In fact, only 10% of the log wood harvested in the country comes from native forests (including the Amazon rainforest), while 90% comes from planted forests. Wood harvested from native forests in Brazil has decreased significantly over the last several years and is quickly being outpaced by wood production from planted forests, as shown in figure 1.

Figure 1. Native forest vs. planted forests wood production (10 years)

* Charcoal, firewood, log wood and pine knot

** Charcoal, firewood and log wood

Source: Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE), adapted by Forest2Market do Brasil

The most important piece of this entire situation is that the above data is virtually unknown throughout Brazilian society at large. This lack of awareness and knowledge is even greater outside the country, where any understanding of Brazil’s geography and natural resources, its primary forest sector and related products, the Amazon region, and national public policies for environmental management is practically non-existent.

Amazon Rainforest Fires

The public debate surrounding the topics discussed above exists almost entirely independent of the current fires that are burning in parts of the Amazon, which have garnered significantly more international media coverage in recent days. We must, therefore, treat the loss of natural forest from fire separately. Fire is an oftentimes highly destructive but natural event that impacts all forests in every corner of the globe, and the Amazon is no different. While the causes of the current fires are both natural and man-made, they are not driven by commercial forestry or forest management practices.

Per recent analysis from NASA’s Earth Observatory, “In the Amazon region, fires are rare for much of the year because wet weather prevents them from starting and spreading. However, in July and August, activity typically increases due to the arrival of the dry season. Many people use fire to maintain farmland and pastures or to clear land for other purposes. Typically, activity peaks in early September and mostly stops by November.”

NASA continues, “As of August 16, 2019, an analysis of NASA satellite data indicated that total fire activity across the Amazon basin this year has been close to the average in comparison to the past 15 years. (The Amazon spreads across Brazil, Peru, Colombia, and parts of other countries.) Though activity appears to be above average in the states of Amazonas and Rondônia, it has so far appeared below average in Mato Grosso and Pará, according to estimates from the Global Fire Emissions Database, a research project that compiles and analyzes NASA data.”

To be sure, the health and preservation of the Amazon’s rainforests is of great importance to the entire world, including the global forest products value chain. However, Brazil's primary forest industry is not responsible for the fires currently burning in the Amazon. As Paulo Hartung, Executive-President of the Brazilian Tree Industry Association (IBA) recently stated, “Fully aware of the social, environmental and economic importance of a preserved forest, the Brazilian Tree Industry Association joins in support of the Amazon, above and beyond political and ideological quibbles. We must unite around a scenario where conservation and sustainable development are compatible.”

Economic Impacts

While the international community’s limited knowledge of Brazil’s forests should not theoretically impact its economy, the constant negative portrayals combined with the president’s oftentimes provocative remarks pose a risk to int ernational trade. For years, Brazil’s primary (legal, responsible, and sustainable) forest sector has driven the small-scale, exploitative (oftentimes illegal) log trade further into the shadows. With a long-term vision and environmental accountability, the primary forest sector has masterfully adapted to the international environmental schema and incorporated many of its initiatives. Presently, environmental conservation in the primary forest sector is no longer seen as a burden imposed by state edicts, but rather as a key component for the success of long-term agricultural and sustainable forestry. This dedication has garnered respect for Brazil’s primary forest industry sector in the international community.

ernational trade. For years, Brazil’s primary (legal, responsible, and sustainable) forest sector has driven the small-scale, exploitative (oftentimes illegal) log trade further into the shadows. With a long-term vision and environmental accountability, the primary forest sector has masterfully adapted to the international environmental schema and incorporated many of its initiatives. Presently, environmental conservation in the primary forest sector is no longer seen as a burden imposed by state edicts, but rather as a key component for the success of long-term agricultural and sustainable forestry. This dedication has garnered respect for Brazil’s primary forest industry sector in the international community.

Hartung noted that “The Brazilian planted forest sector, as well as the modern Brazilian agrobusiness, have a proven record of effective promotion of environmental causes, producing natural, renewable products in a sustainable way.”

However, the wound opened by the recent spate of misinformation combined with photos from Amazonian fires may also damage the image of Brazil’s primary forest sector. Sadly, the lack of cautious and responsible knowledge sharing combined with media hyperbole may lead certain purchasers of Brazilian forest products to review their trade partnerships. Even wood products that are grown or manufactured thousands of miles from the Amazon can carry the stigma of being "Made in Brazil."

This is why Brazil’s forest products industry must emphatically highlight what is really happening: the fires burning in the Amazon have no connection to commercial forestry, and the vast majority of timber production in Brazil comes from trees that are cyclically planted, harvested and replanted, without causing so much as a square centimeter of deforestation. In fact, the opposite is occurring.

The planted forests segment, in particular, contributes most to the increased conservation of Brazil’s native forest environment. For each hectare of forest that is planted for timber production purposes in Brazil, the segment conserves 0.7 hectares of native forest—a percentage well above the legal obligation. Which means that, for the 7.8 million hectares of pine and eucalyptus that have been planted in the country, 5.6 million hectares of native forests have been conserved.

Like many of the emotional debates connected to global environmental challenges, many layers of complexity surround the current fire situation in the Amazon. While potential solutions can seem equally challenging, Forest2Market do Brasil echoes Executive-President Hartung’s words in encouraging fruitful dialogue and progress: “We cannot allow that decades of hard and devoted work carried out by the private sector, the academy, by researchers, public servants and environmentalists be suddenly wasted.”