In a recent meeting with members of the forestry community, Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Administrator Scott Pruitt said that the Agency issued a “statement of policy making clear, that future regulatory actions on biomass from managed forests will be treated as carbon neutral when used for energy production at stationary sources.” The statement went on to add that “The use of biomass from managed forests can bolster domestic energy production, provide jobs to rural communities, and promote environmental stewardship by improving soil and water quality, reducing wildfire risk, and helping to ensure our forests continue to remove carbon from the atmosphere.”

In the wake of the meeting, a number of media outlets and NGOs took issue with the Agency’s statement on the carbon neutrality of forest biomass. In a breath of fresh (objective) media air, Smithsonian attempted to address the complexity of the situation. While largely accurate in its broad treatment of the subject, it does, however, miss the mark in its premise that biomass use prompts mass deforestation; this fallacy was dispelled and illustrated in great detail in Forest2Market’s 2015 study for the U.S. Endowment for Forestry and Communities, National Alliance of Forest Owners (NAFO) and the U.S. Industrial Pellet Association (USIPA).

The Smithsonian article, “The EPA Declared That Burning Wood Is Carbon Neutral. It’s Actually a Lot More Complicated,” notes that there are “five things to know about the controversial change.” Those five issues are included below (verbatim) with added commentary by Forest2Market. (Since forest biomass and, by extension, industrial wood pellets are the primary point of contention—a vast majority of which are manufactured in the US South with local forest resources—we will limit our commentary to data that is also unique to the US South.)

- Biomass is only sustainable on long time scales.

Smithsonian: “The idea that forest biomass is carbon neutral is not wrong. Trees absorb carbon from the atmosphere as they grow. So if a tree is burned for fuel, the thinking goes, another can be planted to replace it. And then that replacement tree should eventually re-absorb the carbon.

But while burning wood immediately releases carbon, it takes decades or even a century for a replacement tree to absorb the same amount of carbon. In the meantime, all that atmospheric carbon will continue to drive climate change.”

Forest2Market: Important energy and natural resource decisions can only be made over long time periods; consider how many decades the world has relied almost exclusively on non-renewable fossil sources of energy, the social costs of which are a detriment to us all.

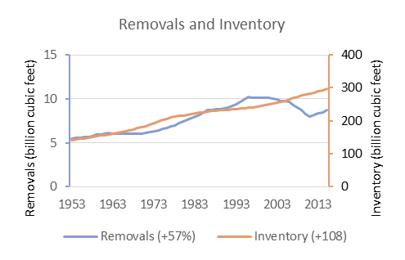

Scientists in forest-related industries and groups such as the National Council on Air and Stream Improvements (NCASI) recognize the difference between biogenic and non-biogenic sources of energy. Combusting fossil (non-biogenic or below ground) sources of carbon (coal, oil, natural gas) adds to the carbon dioxide content of the atmosphere because these resources are “captured” and released from within the earth. Combusting renewable woody biomass (biogenic or above ground) carbon, however, adds little to no net carbon dioxide to the atmosphere when considered over the long-term. As long as we are not depleting forest inventories, which we currently are not, this biogenic carbon is reabsorbed by new plant life as it grows; it is a sustainable and cyclical process.

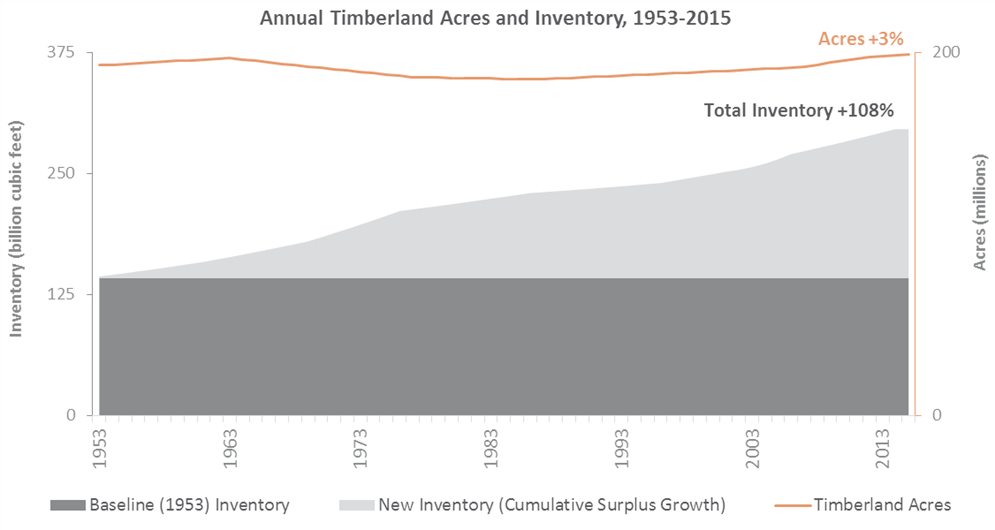

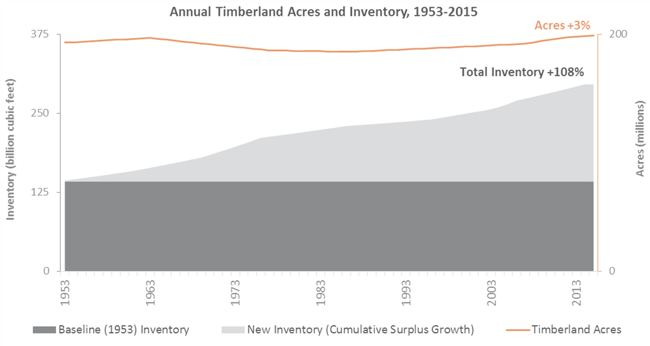

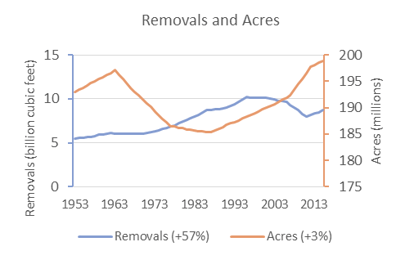

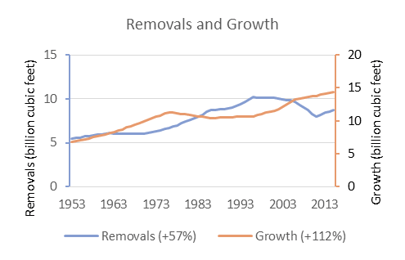

Trees do take years to grow into merchantable timber suitable for harvest. However, since the middle of the twentieth century, the amount of timberland—unreserved, productive forest land—in the US South has increased by about 3 percent. Between 1953 and 2015, economic growth and increased construction spurred consumer demand for forest products, which led timber harvests (or removals) to increase by 57 percent. Yet over this same period, the amount of wood fiber (or inventory), and thus the amount of carbon stored in Southern forests, increased 108 percent.

Current timberland acreage in the US South covers 198.9 million acres, a net increase of 5.8 million acres (3 percent) since 1953. On average, growth has exceeded removals on US South timberlands by 38 percent since 1953. Because growth predominantly exceeded removals, the forest inventory of the US South continuously increased and more than doubled from 142.1 billion cubic feet (BCF) in 1953 to 296.1 BCF in 2015. A larger forest volume means more stored carbon. (Detailed data, charts and additional information available here.)

- Forests need proper management to remain carbon neutral.

Smithsonian: “Even if a tree is planted for every tree converted to fuel pellets, trees regrown on plantations don’t store the same carbon as natural forests. One recent study suggests it would take 40 to 100 years for a managed forest to capture the same amount of carbon as a natural forest. And since most plantation forests are harvested at 20 year intervals, they will never make it to the carbon-neutral point.

There are also no guarantees, laws or regulations that require managed forests to grow to the carbon-neutral point, the Post points out. In fact, it’s even possible that cleared forest land could be converted to agricultural use, which would give biofuels a massive carbon footprint. Also not included in carbon calculations are all of the additional emissions released during logging and shipping the wood pellets across the globe.”

‘Unless forests are guaranteed to regrow to carbon parity, production of wood pellets for fuel is likely to result in more CO2 in the atmosphere and fewer species than there are today,’ William Schlesinger, President Emeritus of the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies writes for Science.”

Forest2Market: Working forests play an important role in keeping forested land forested. However, land use conversion in the US South has been a growing concern in recent decades, resulting in the permanent deforestation of millions of acres of forestland. Between 1982 and 2012, developed land increased by 19.3 million acres (79.9 percent) from 24.2 to 43.5 million acres in the US South. This means that around 46 percent of the conversion to development that occurred in the US during this period occurred in the South, an area that comprises just 22 percent of US land area.

Properly-managed plantation forests in the US South are typically “thinned” twice before being harvested around the 30-year mark (rather than 20-year intervals), and many millions of timberland acres throughout the South are substantially older than that. While hardwood growth rates in colder climates are certainly longer than they are in the US South, modern tree genetics and silviculture techniques are able to maximize growth volumes and growth times, sequester more carbon and, most importantly, keep forested land forested.

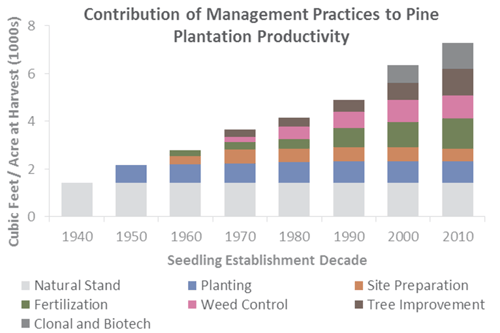

Detailed research over the last 50 years, which was conducted in partnership with the US Forest Service, university forestry departments, state agencies and industry partners, has resulted in fact-based improvements to forest management practices, including site preparation, fertilization, weed control and thinning. These efforts have also enhanced the quality and survival of seedlings.

The result of these improvements has been an astounding nearly fourfold increase in the amount of growth achievable for seedlings established in the 2000s compared to seedlings established in the 1950s. Largely because of the implementation of these practices on privately-owned lands, total annual timberland growth in the US South increased 112 percent between 1953 and 2015, and growth exceeded removals by 38 percent on average. Healthy demand has made it easy for corporate and family landowners to take a long-term view, investing in more expensive management practices up front for greater returns in the future. Most importantly, stable demand from the forest products industry helps protect forestland from its greatest, irreversible threat: urbanization.

- Carbon emissions don’t just come from burning.

Smithsonian: “As Emma Grey Ellis at Wired reports, forest carbon is not just stored in their wood—a large amount is stored in the soil. And you can’t take the branches without impacting the soil, Sami Yassa, senior scientist at the Natural Resources Defense Council, tells Ellis.

Soils can hold up to twice as much carbon as the trees above, depending on the type of forest and amount of leaf litter and debris on the forest floor. Exposing that material to more light and elevated temperatures spurs faster microbial breakdown of the soils and release of stored carbon. One 2017 study suggests forest soils are already giving off more carbon as the world warms.

‘If a significant amount of that soil carbon is added to the atmosphere, due to microbial activity in warmer soils, that will accelerate the global warming process,’ study author Jerry Melillo of the Marine Biological Laboratory says. ‘And once this self-reinforcing feedback begins, there is no easy way to turn it off. There is no switch to flip.’”

Forest2Market: In the world of environmental science, there is little agreement when it comes to standardized testing methodologies, measurement criteria, metrics, etc. New data is always emerging, which can drastically challenge the previously-held standards.

For instance, a 2016 study found that the radiocarbon dating of soils (when combined with previous accepted models of carbon testing), overestimated the carbon sequestration potential of those soils by as much as 40%. A Guardian piece published upon the study’s release notes that “Scientists from the University of California, Irvine (UCI) found that models used by the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) assume a much faster cycling of carbon through soils than is actually the case. Data taken from 157 soil samples taken from around the world show the average age of soil carbon is more than six times older than previously thought.”

However, a 2018 study published recently in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences notes that one way to compensate for a forest’s declining ability to store carbon after harvest—if this capacity is indeed diminished—is to add more trees. Actively replanting after both harvests and natural disturbances like wildfires, pest and disease infestations, and allowing forests to overtake unused cropland can help add tree volume, maintain soil composition and minimize the release of stored carbon.

"The topsoils of reforesting lands provide a significant long-range solution to the problem of the declining carbon-sink strength of U.S. forests, and they help to mitigate climate change,” said University of Michigan ecologist and biogeochemist Luke Nave, the study's lead author. “Even modest increases in the amount of land being reforested would have a multiplicative impact on nationwide carbon sequestration."

Nave’s team of researchers found that reforesting topsoils across the country are currently sequestering between 13 - 21 million metric tons of carbon each year, which is equivalent to roughly 10 percent of the total US forest-sector carbon sink. Over the next century, reforesting US topsoils will sequester a cumulative 1.3 - 2.1 billion metric tons of carbon, accounting for nearly half of the soil-carbon sequestration on US forestland. The amount of stored carbon could increase dramatically with active reforestation efforts on both public and private forestland.

Regardless of the best available science of the day, reforestation and growing more trees is good for our environment—including the soil—which is why working forests have an increasingly important role to play. As the European Biomass Association (AEBIOM) has noted via its research, the effect of a managed forest as a CO2 sink is ten times that of the primary forest. The reasons for this speak to the significance of proper forest management:

- An unmanaged forest will emit almost as much CO2 as it absorbs over its life cycle due to natural degradation. Since no wood was harvested in the end, no substitution effect (trading energy for carbon storage) resulted.

- An unmanaged forest that is destroyed due to natural causes (fungus, insects, fire, etc.) will actually have a detrimental effect by releasing large amounts of carbon. This process makes for a much slower decomposition/regeneration of the forest and its ability to offset carbon debt.

- Managed forests sequester more carbon through growth than is extracted through harvest. In the case of regenerated forestland, carbon stocks are maintained or increase over time, creating zero carbon debt.

Harvesting timber from a mature working forest requires the use of heavy-duty and highly-specialized machinery. While modern harvesting operations take every effort to minimize their “footprint” (read individual state data regarding best management practices here), some of the forest topsoil will be disturbed during a harvest. There is simply no way around this.

Warmer climates and soils may indeed be a concern for the future, and much of the science seems to point in that direction. However, fossil energy sources are 100 percent non-biogenic and non-renewable. A repudiation of viable, plentiful and proven renewable sources of energy—like woody biomass—seems short-sighted given the world’s modern energy demands, and especially if it results in increased reforestation efforts.

- The EPA has not yet completed its scientific analysis.

Smithsonian: “As the Post reports, the announcement comes before the EPA’s Science Advisory Board has finished its deliberations. This is something that the EPA acknowledges in its press release, which states that the board’s process has not yet resulted in a ‘workable, applied approach.’ But according to its policy statement on the matter, the EPA claims that the change will boost rural economies and the timber industry as well as reduce pests and wildfires.

As Miranda Green at The Hill reports, labeling biomass as ‘carbon neutral’ has political element to it. Members of Congress have long pushed for this redefinition for economic reasons.”

Forest2Market: Declaring a policy position before being able to turn the policy into a program is not an argument against the policy itself. Listing the known benefits of the policy, even if they are not strictly environmental in nature, is also not an argument against the policy. The EPA has long considered economic concerns in matters of policy; in fact, they are often required to perform cost–benefit analyses as a routine part of the regulatory process.

When it comes to forests, environmental and economic concerns can often seem irreconcilable. Those unfamiliar with forestry and silviculture practices oftentimes approach this subject believing that there is either one advantage or the other, but not both. This simply isn’t true. Forest2Market’s 2015 study showed that environmental and economic sciences can work together. Keeping forested lands forested is the goal for both concerns; what is good economically for rural communities and the timber industry is also good for the nation’s forests.

The fact is every piece of language that emanates from Washington has a political element to it, and political tides shift very quickly in this country. That said, most would agree that the industrialized world needs to expand its energy portfolio in order to taper its reliance on fossil energy, and biomass has an important role in that expansion. Even as technology continues to improve energy efficiencies, biomass has historically served as a reliable energy bridge to new and better technologies. While the carbon footprint of woody biomass is larger than some other renewables, it is still one-fifth to one-tenth that of fossil-based fuels, and it is derived from renewable forest resources. Ignoring our long-term energy needs and refusing to diversify our energy portfolio is not a sustainable political position—regardless of which political party is in charge at any given moment in time.

- Reliance on wood could spark widespread clear cutting.

Smithsonian: “The European Union is already relying on burning wood as a “carbon neutral” energy source to meet Paris Accord emission goals. And one of the big arguments used to support this switch to wood is that the industry would rely on the limbs, chips and sawdust produced by logging and milling that would already be incinerated. But in reality, that’s not what’s happening.

As Fred Pearce at Yale Environment 360 reports, the demand for wood pellets has sparked an increase in logging in the American south and across Europe. It’s also fueled illegal old-growth logging in ecologically sensitive areas, including the Carpathian Mountains of Romania and national parks in Slovakia.

The demand for pellets is only increasing, Pearce reports, jumping 40 percent between 2012 and 2015 alone. As more climate-conscious countries, like Japan, South Korea and China begin to use this wood pellet ‘loophole,’ logging will continue to expand, likely undermining the climate goals the regulations are intended to support.”

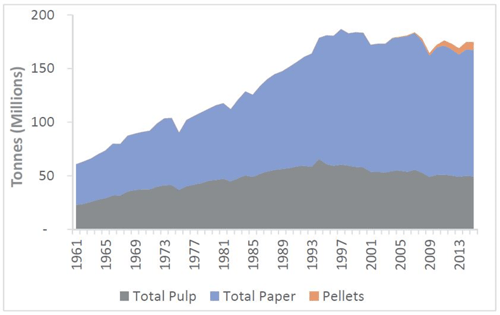

Forest2Market: The rise of the wood pellet market over the last decade has caused some to question the impact that pellet mills are having on forest inventory in the US South. However, pulpwood harvests for export facilities are but a small fraction of overall harvests when compared to harvests for non-pellet facilities, and claims that this impact is disastrous are largely exaggerated.

The export of industrial wood pellets produced in the US South to meet renewable energy goals in the European Union is not a threat to the sustainability of Southern forests and will not result in “widespread clear cutting.” Forest2Market’s 2015 report reveals that industrial pellet exports represent a very small part of forest harvests in the US South and will continue to do so into the future.

- Total removal of wood in the US South for all markets is 3.3 percent of the total forest inventory.

- Pellet exports represent 0.08 percent of the total inventory.

- In 2014, pine removals for industrial pellet production totaled 3.7 million tons or 0.3 percent of the pine pulpwood inventory and 0.09% of the total pine inventory.

- In 2014, hardwood removals for industrial pellet production totaled approximately 2.4 million tons or 0.2 percent of the hardwood pulpwood and 0.06 percent of the total hardwood inventory.

- In 2014, pellet exports from the US South to Europe, which represent the vast majority of US pellet exports, were 3.6 million metric tons, or 40 percent of Europe’s 9 million metric ton industrial pellet consumption.

- Future industrial demand for US pellets overseas represents 0.3 percent of total forest inventory in the US South.

- Realistic demand and market share outlooks show that US industrial exports of biomass pellets to Europe could eventually rise to 10.8 million metric tons.

- Annual removals to meet this demand would total 25 million tons, which represents 1.0 percent of pulpwood inventory and 0.3 percent of total forest inventory in the South.

Demand from the forest products industry has not resulted in dramatic losses to the South’s timberlands. Quite the opposite is true, in fact, as shown by the historical data, which documents increases in timberland removals, acres, growth and inventory, and Forest2Market’s independent statistical analyses. Statistical analyses show that increased demand in the US South is associated with more acres, better growth and larger inventories. These relationships are strong and statistically significant.

Kudos to the Smithsonian for advancing the cause of dialogue related to a complex and admittedly contentious topic. However, the data clearly show that sustainably-harvested, working forests are essential to our shared environmental and economic interests, and to increasing the renewables portfolio of our growing energy needs. Strong demand for forest products incentivizes landowners to maintain their timberlands and invest in forest productivity in order to increase supply, which has resulted in more wood growing (and carbon stored) in US South forests. The future of forests depends on healthy demand for forest products, including woody biomass. Despite the current political language being used in Washington, this demand is vital for keeping forested lands forested and for diminishing the irreparable threat of urbanization.