3 min read

The Economics of Pulpwood Supply: New Markets are Essential

Stan Parton

:

February 11, 2021

Stan Parton

:

February 11, 2021

Timber and the land timber occupy are economic assets. As in any market, when there is strong demand, owners actively manage their assets to maximize economic return. In this case, timberland owners manage their forests to maximize tree growth, especially the growth of the highest valued product – sawtimber. This management structure increases their return on investment. In turn, forest products manufacturers use the raw materials that they purchase to the fullest extent possible, including the utilization of low-value trees and residuals for energy purposes where market exist.

The growth of the forest products industry - including the renewable biomass sector - continues to create new demand for wood raw materials, which has resulted in an increase, rather than a reduction, in forest inventory. These new markets are imperative for keeping the supply/demand of forest raw materials in balance, especially since southern forests have been oversupplied for the last decade.

Forest Management 101

While much of the feedstock material used to produce biomass and wood pellets consists of wood chip residues generated from other wood products manufacturing processes, it is important to clarify that many pellet producers also use low-value pulpwood in the manufacturing process. How are harvested trees routed through the forest supply chain?

The sizes of the trees removed from timberland are quite different, serve a range of needs, and therefore vary in value. In general, southern pine logs fall into one of the following categories:

- Logs 5”-7” diameter at breast height (DBH) are considered “pulpwood”

- Logs 8”-11” DBH are considered “chip-n-saw” (CNS)

- Logs 12”+ DBH considered “sawtimber”

Timberland owners in the US South who manage their land for timber production have historically managed for large diameter, high-value sawtimber logs. Centuries of demand for solid wood products used for structural purposes has driven this paradigm, as larger logs result in better yield and quality in solid wood product manufacturing. Landowners are therefore incentivized to grow larger logs through high price offerings for the sawtimber from solid wood product manufacturers. As such, timberland management practices have evolved over time to maximize real returns on large logs, with landowners implementing silvicultural prescriptions to yield larger, high-value logs faster.

One such management practice known as “thinning” involves removing low-value pulpwood (generally small, misshapen, deformed and off-species) trees. This process reduces competition for soil nutrients and opens the forest canopy to allow more sunlight into the timber stand, which induces higher growth rates for the remaining high-value trees. These trees continue to grow until reaching larger diameter and quality specifications to be considered for solid wood product manufacturing.

The Economics of Wood Consumption

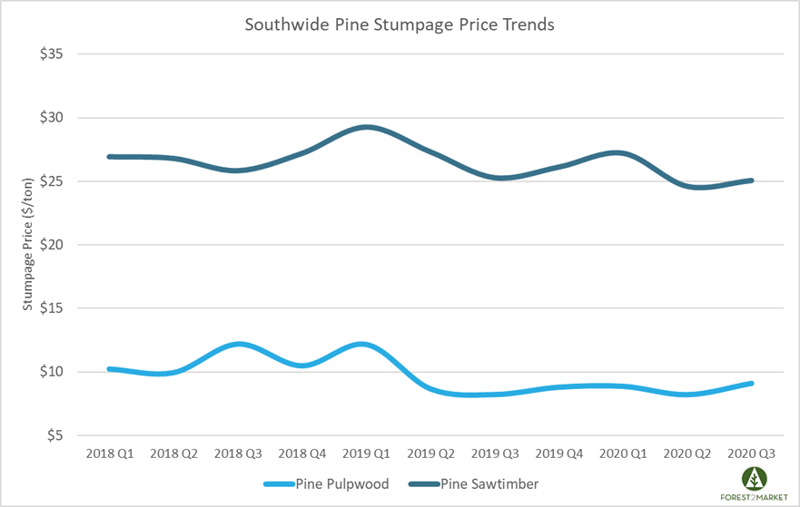

Basic economics and industry best practices ensure that harvested trees are used to maximize their value. Consider the price differential between sawtimber and pulpwood: In 3Q2020, the southwide volume weighted average price (stumpage) for pine sawtimber was roughly $25/ton, and the southwide volume weighted average price of pine pulpwood was roughly $9/ton.

Timberland owners will not harvest all of their timber as small trees at $9/ton when they can harvest mature trees at $25/ton. In addition to the higher value for larger logs, the increased growth of the trees in the intervening years also results in several additional tons of sawtimber that can be sold at the higher price. Economically, it makes no sense to do otherwise.

Therefore, there are three important points to understand about the economics of pulpwood supply:

- Pulpwood is the lowest-value, smallest-diameter product that can be removed from a stand of timber.

- While the incremental cash flows from pulpwood sales are not the primary motive for thinning, demand for pulpwood results in incremental cash flows for timberland owners. The relative stumpage price differential between pulpwood and sawtimber upholds the justification for managing timberland to yield more sawtimber.

- This also ensures pulpwood harvests remain a result of land management prescriptions as opposed to the incentive to manage for pulpwood production.

The Importance of New Markets

The wood pellet industry is dwarfed by the traditional forest products industry. In the US South, roughly 280 million tons of logs are harvested each year. Approximately 145 million tons go to pulp and paper mills as pulpwood; approximately 120 million tons go into dimensional lumber and panel/plywood production as CNS and sawtimber; and roughly 15 million tons of harvested roundwood go into the production of wood pellets. Roundwood used for pellet production represents only 10% of the small diameter roundwood harvested.

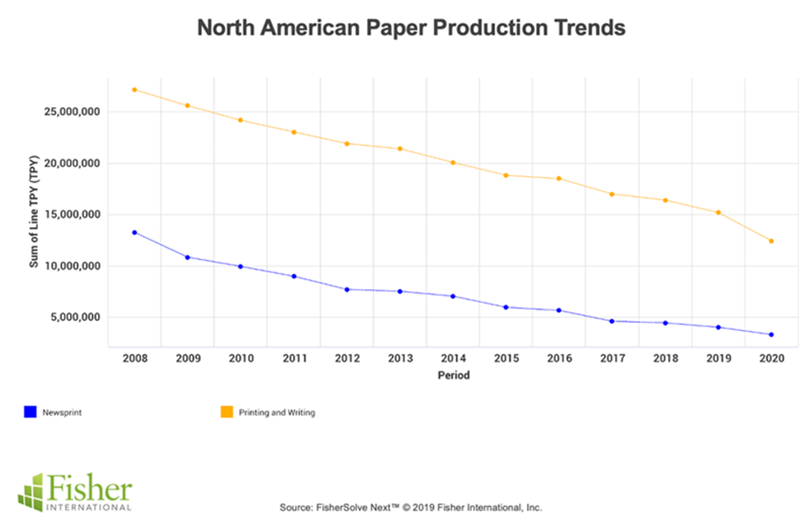

While the growth of e-commerce has increased demand for packaging and shipping boxes, demand for printing and writing papers is declining 6% annually and is expected to continue. In 2017 alone, newsprint demand was down 10% from the previous year and most of the newsprint plants in the US South have been closed or converted to other products such as lightweight linerboard where possible.

But for southern landowners who have made the long-term investments necessary to significantly improve forest productivity and increase inventory on a stable land base, the wood pellet industry has opened up new markets for their low-value, small diameter timber. In a dynamic economy, these outlets are imperative to ensuring the long-term viability of managed timberland. The result is an environmental/industrial relationship that produces valuable products that we have all come to depend upon, while also using low-value materials for beneficial purposes where markets exist.

An increase in forest stocking levels is the ultimate environmental benefit, which naturally occurs when landowners manage their timber resources for economic purposes. It is this symbiotic relationship that, most importantly, incents timberland owners to keep forestlands forested and invest in advanced timber management practices, which provides both economic benefits to the timberland owner and environmental benefits to all of us.

When forestland ownership becomes uneconomical, the risk for converting the land to other uses increases. With such conversion, the forest is lost forever. Keeping the economics of forest ownership strong, including the utilization of low-value forest materials, is a key component in preserving the proven relationship between environmental and economic interests of the forest.