This post was written by Stephanie Siegel, USDA Forest Service Contract Science Writer, and originally published at Compass Live, the blog of the U.S. Forest Service’s Southern Research Station.

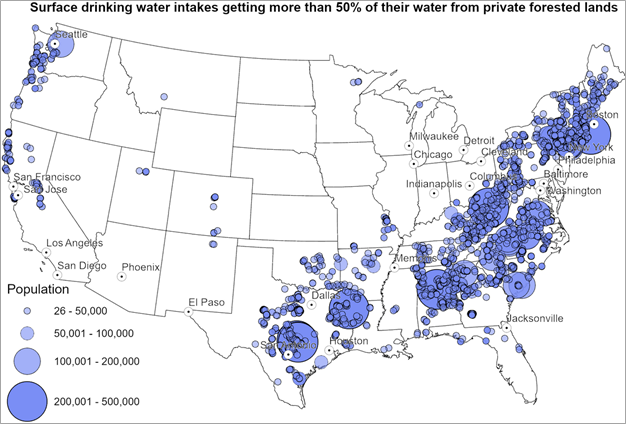

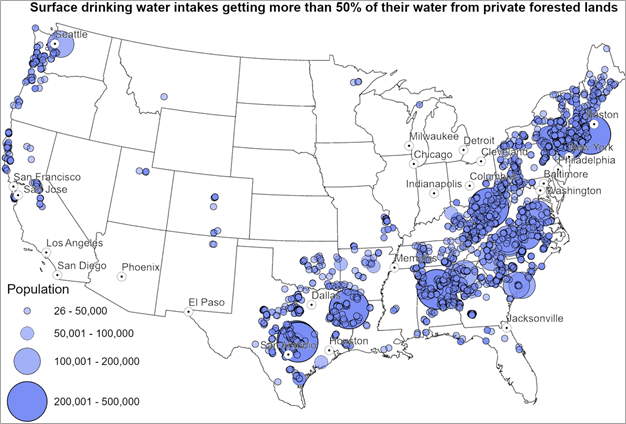

Forests provide cleaner water than any other land cover type. Around 60 million people in the U.S. get more than half of their surface drinking water from forested lands. In Environmental Research Letters, USDA Forest Service ORISE hydrology fellow Ning Liu and colleagues break down the contributions of U.S. forests to surface drinking water supplies.

Their map tracks where water originates on all forests in the lower 48 states (88,000 watersheds) and along each river network to utilities’ drinking water intakes. Privately owned forests provide more than half the water supply for 16 million people in the eastern U.S. Some surface drinking water intakes serve large populations and receive more than 20 percent of their water supply from forested lands.

“Dr. Liu laid the groundwork in identifying what populations are depending on forests for their drinking water supply,” says Peter Caldwell, research hydrologist and the study’s principal investigator.

Liu created a snapshot of current conditions. Then he combined the EPA Integrated Climate and Land Use Scenarios (ICLUS v2.1) with a map of current water sources and users to identify those that could face significant loss of forests upstream.

Atlanta, GA; Birmingham, AL; Charlotte, NC; Greenville, SC; Nashville, TN; and Richmond, VA all get drinking water from forest lands. USDA Forest Service image.

Atlanta, GA; Birmingham, AL; Charlotte, NC; Greenville, SC; Nashville, TN; and Richmond, VA all get drinking water from forest lands. USDA Forest Service image.

“Looking ahead, we may see less forested land area, and more water coming out of an urban landscape,” says Caldwell of the southeastern U.S.

Southerners are more likely to have their water supply degraded when forests are lost to suburban sprawl. That’s because private forests are most likely to be developed, and in the South, more than 80 percent of forest lands are privately owned. In 2012, the Southern Forest Futures Project estimated that 23 million acres of southern forest would be replaced by urban land uses by 2057.

Much of the projected forest loss is in Alabama, Georgia, Mississippi, and the Carolinas. Downstream of such threatened forests nationally, around 5,600 surface drinking water intakes in 2,105 communities serve 50 million people. Utilities that lose their upriver forests will also lose an effective filtration system. Water that runs off forests needs less cleaning than urban runoff to make it safe to drink. Water from towns and farms has more sediment and chemicals and therefore costs more money to treat to drinking water standards.

Also, households and their sewers contain drugs like antibiotics that traditional water treatment methods cannot remove. Newer technologies, like granular activated carbon or ozonation, are available but expensive. “In some cases it could be more cost-effective to protect the water source than to build bigger and better water treatment plants,” adds Caldwell.

Some utilities think so, too. They have bought forest lands, while others are partnering with land trusts. The funds come from green bonds, federal grants, and watershed protection fees.

“Water from forests is of good quality and easier to treat compared to water from other land uses,” says Caldwell. This is an ecosystem service that private forest landowners provide for downstream communities in the South, however, they typically are not compensated for this service.

“It’s important to start thinking about how private forest landowners could be supported for the ecosystem services they provide so that they can keep their forested land forested rather than converting it to other more profitable land uses or selling it to be subsequently developed,” says Caldwell.

Caldwell named two groups focusing on this work along with the USDA Forest Service: the Southeastern Partnership for Forests & Water and a 13-state southern forest conservation initiative called Keeping Forests.

Caldwell serves on a subgroup of Keeping Forests that thinks of ways to compensate landowners for ecosystem services that forests provide—like clean water. “People are getting behind this idea, especially in the South,” says Caldwell.

While this study looked at water supply from forests, new research is examining water quality from forest lands and linking that to water treatment costs. The current publication follows up the research team’s 2020 technical report on water from southern forest lands, which includes a story map for each southern state.

“Forests are important for water supply. There’s a large population across the U.S. that’s dependent on water from forest lands. It’s important to consider downstream users of water from forests, and there could be economic benefits for keeping forests on the landscape,” says Caldwell.