As we noted in the comprehensive study recently completed for the National Alliance of Forest Owners (NAFO), the economic impact of private, working forests on the US economy is tremendous. The total direct, indirect and induced employment effect associated with private timberlands is around 2.5 million jobs, $109.4 billion in annual payroll and $288 billion in sales and manufacturing. Consequently, the harvest and subsequent regeneration of trees is of the utmost importance for the US forest industry, and the most effective way to ensure this growth/harvest cycle is sustainable over time is to keep forested lands forested.

Despite the perception by some that the US forest products industry is irreparably destroying America’s timberlands, nothing could be further from the truth. Per recent data from the US Forest Service’s Forest Inventory and Analysis (FIA) Program, forest and woodland area in the United States has plateaued at 823 million acres following decades of expansion. Forest and woodlands now comprise over one-third of the US landscape and contain 1 trillion cubic feet of wood volume. Forest2Market’s own research has also demonstrated repeatedly that increased demand for wood products results in increased forest inventory.

When it comes to forests, environmental and economic concerns can often seem irreconcilable. Those unfamiliar with forestry and silviculture practices oftentimes approach this subject believing that there is either one advantage or the other, but not both. This simply isn’t true, and any claim that America’s trees are used for anything less than their full potential is ill informed. Landowners manage their forests to maximize tree growth and, subsequently, their return on investment. In turn, forest products companies use the trees they buy from those landowners to the fullest extent possible because it makes both financial and environmental sense.

How are Trees Utilized?

In the US South, pine trees are considered mature at 25-40 years old. Plantation stands of trees (acreages of trees that are continuously planted, harvested and replanted) are typically “thinned” when trees are 12-15 years old; thinnings remove only a portion of the stand’s smaller trees to make more room for the more desirable trees to grow larger. Trees that remain are often thinned again when they reach 18-22 years of age. The total number of thinnings, volume harvested during each thinning, and the timing of each thinning in the total growth cycle will affect the overall volume on the stand.

When trees reach a diameter large enough to produce high-value wood products, a final harvest takes place. It’s important to note that the sizes of the trees removed during thinnings and final harvests are quite different. In general, the size of pine logs fall into the following categories:

- Trees that are 5”-7” diameter at breast height (DBH) are considered “pulpwood”

- Logs that are 8”-11” are considered “chip-n-saw”

- Logs that are 12”+ in diameter are considered “sawtimber”

As logs get larger, the per-ton value of the trees typically increases; sawtimber that has a DBH of 18" is more valuable than 12" sawtimber, for instance. The raw materials that result from a timber harvest, then, are sawtimber (including chip-n-saw), pulpwood, and harvest slash.

The Economics of Tree Utilization

Basic forest economics and industry best practices ensure that harvested trees are used to maximize their value. Consider, for example, the price differential between sawtimber and pulpwood. In 1Q2019, the southwide volume weighted average price for pine sawtimber was $28.70 per ton. The southwide volume weighted average price of pine pulpwood was $11.88 per ton. Landowners choose to manage their timber for different strategic goals but in general, most landowners will not harvest small trees at $11.88 per ton when they can harvest mature trees at $28.70 per ton. Not to mention, the additional growth of the tree in the intervening years results in many more tons of sawtimber that can be sold at the higher price and turned into a higher-value wood product.

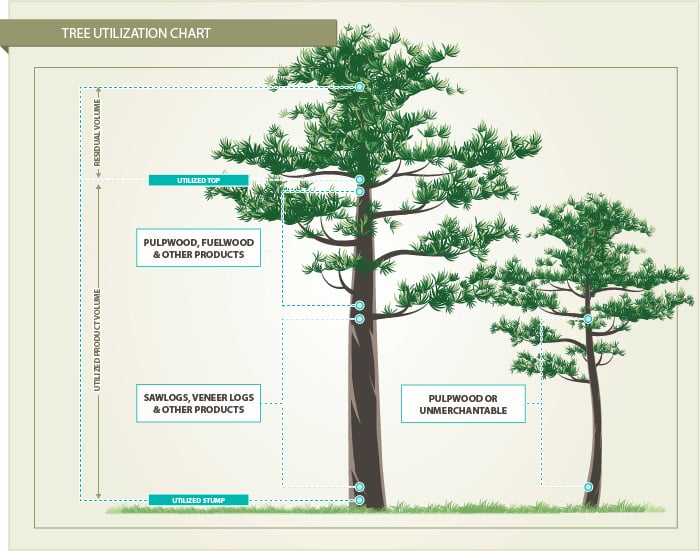

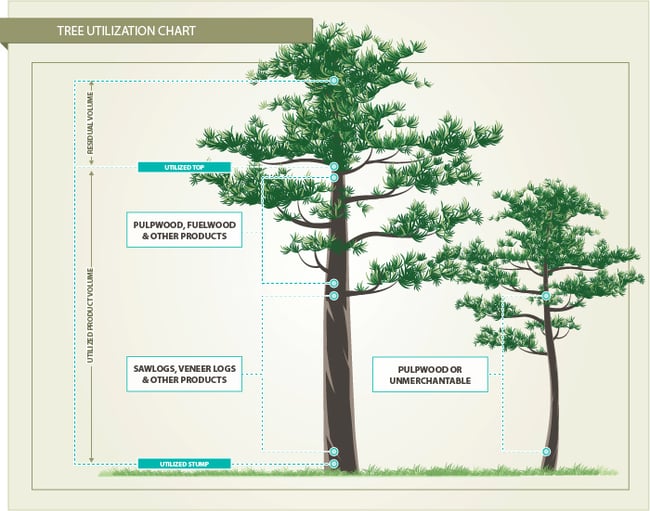

The following infographic illustrates typical forest inventory utilization in the US South.

Sawlogs, Veneer Logs & Other Products

The larger of these two trees is a long-leaf pine tree that is mature—between 25-40 years old. On the younger end of this spectrum, the tree would be considered sawtimber sized, ideal for lumber production. At the older end of the spectrum, this tree might be appropriate for the production of plywood or veneer. Older trees have grown to the large diameter size needed to create large sheets of wood by peeling the tree from the outside in. These sheets are used as the layers (or plies) of plywood or as veneer to cover furniture or cabinets. This portion of a mature tree, which runs from the stump up through the smallest diameter that can be used for producing these products, comprises the vast majority of the tree’s volume. It is from this section of the tree that longstanding wood products (building products, furniture, etc.) are made—products that continue to store part of the tree’s carbon stock for decades.

Because timber is sold by the ton in the South, it is the value in this part of the tree that leads timberland owners to make the decision to sell. Sawtimber, plylogs and veneer logs are among the highest value products that come out of the forest. For a vast majority of timberland owners, whole mature trees are typically only harvested when they are large enough to bring higher prices. Economically, it makes no sense to do otherwise.

Pulpwood, Fuelwood & Other Products

The rest of this mature tree, labeled Pulpwood, Fuelwood & Other Products, is too small in diameter to make lumber. Once the tree has been harvested for large-diameter material, the rest of the tree can be used to make a wide range of products that also continue to store carbon into the future, such as OSB and a variety of pulp and paper products, including cardboard boxes and other packaging materials that can be recycled. This section of the tree can also be chipped for domestic electricity generation or dried and formed into wood pellets for heating and electricity markets.

Utilized Top & Residual Volume

The rest of the mature tree is often called harvest slash. It is made up of the top, limbs and pine needles. In general, this material serves one of two purposes:

- Best management practices require that roughly one-third of this material be left on the forest floor to prevent erosion, nourish the soil and provide habitat for wildlife.

- The rest is often used by sawmills, pulp and paper mills and pellet facilities to generate heat and electricity to run their own operations. Some even sell excess electricity back to the power grid.

Pulpwood or Unmerchantable

And what about the smaller tree on the right? The first thing to notice about this tree is its trunk. Because there is a bend in the trunk, this tree will never grow to become a higher-value sawtimber tree. While the gang curve saw and other technological improvements have made it possible to produce lumber from larger crooked trees, these trees are not ideal for maximizing output and efficiency. Lumber can be most efficiently produced from trees with straight trunks. As a result, many of the smaller curved trees on a stand of managed timber will be removed during a thinning. Remaining trees—both large and small—that contain bends, twists, hollowed centers or other defects will be removed during a final harvest along with the sawtimber.

Over time, the forest industry has vastly improved technology and expanded into new areas just to make sure that trees harvested on its behalf are highly utilized. In the 1990s, for instance, it took the average sawmill 5.0 - 5.2 green tons of wood to make 1,000 board feet (1 MBF) of lumber. With the advent of a host of new technologies—including increased automation, continuous kilns and precision business information systems—the average today is 4 green tons of wood per 1 MBF, and some mills have even reduced their consumption to 3.5 green tons per 1 MBF.

In addition, companies throughout the forest industry have found creative means of using their waste streams. Decades ago, mills began running their kilns and other processes with their own wood waste instead of fossil fuels—a trend that is still widely practiced today. They installed wood boilers that use the bark, harvest slash, and other mill residues to generate the heat and electricity needed to dry lumber and wood chips or run paper machines.

The forest products industry—including wood, paper and energy products manufacturers—takes the harvesting and regeneration of trees very seriously. As noted above, the entire forest value chain has evolved over time to efficiently utilize every single part of a harvested tree. The result is an environmental/industrial relationship that generates very little waste and produces valuable products that capture carbon. It is also a symbiotic relationship that, most importantly, ensures that forested lands remain working forests for future generations.