As European countries continue to expand their energy portfolios to include more bioenergy production via industrial wood pellets, manufacturers throughout the Southeast are helping meet the demand. But the trend is not without its detractors. The Associated Press (AP) and North Carolina news source WRAL both recently published articles largely critical of the wood pellet industry. Sadly, both pieces do not provide a full-spectrum view of the forest supply chain or the environmental benefits of sustainably managed forest resources.

The disconnect tends to resurface in the debate surrounding the use of woody biomass for renewable energy, including power generation and biofuels. The primary point of contention is typically framed as: “Burning trees is permanently decimating Southern forests.”

Part of the problem lies with the definition of “trees.” Small, low-vigor trees, sometimes called pulpwood, require removal from actively managed forests to allow healthy and larger trees to thrive. These larger trees eventually grow to become high-value sawtimber used to make lumber for homes and other structures. This silvicultural procedure is centuries old and remains a forestry best practice endorsed by states, national governments, as well as the UN FAO, mainstream NGOs and others.

While we (and many others) have addressed this point of contention numerous times with science and data, the WRAL piece referenced above contains outright misinformation, noting that: “The growing [wood pellet] industry clear-cuts forests – about 60,000 acres a year in North Carolina alone – for the pulp to process.”

This statement alone is inaccurate on every level.

- The wood pellet industry does not clearcut forests. A majority of both the physical and economic timber harvest goes to other forest products facilities such as sawmills or paper mills, and it is the combination of each of these markets that drive harvest decisions. As one manufacturing input of many, the pellet industry utilizes roundwood in the form of pulpwood that is also removed during a scheduled harvest of large, high-value trees. Pulpwood typically comprises +/-30% of the volume from a sawtimber harvest; it is a “come-along” byproduct of a final harvest, not a primary incentive for harvest.

- The wood pellet industry does not clearcut 60,000 acres of North Carolina forests annually. Again, pulpwood is a byproduct of a sawtimber harvest. While the total number of private North Carolina timberland acres harvested annually varies, it is wildly inaccurate to suggest that 60,000 acres of pulpwood is harvested for the production of wood pellets. It would be more accurate to say that NC’s wood pellet producers use the wood waste and pulpwood removed from roughly 60,000 acres of private timberland harvests, which would equate to +/-30% of the volume from those harvests.

- Wood pellet manufacturers do not process pulp: Pellet manufacturers process lots of low-value wood raw materials, including wood chips and sawdust, waste wood, as well as pulpwood. “Pulp” is a finished product typically used in the paper industry; it is neither a viable manufacturing input—nor an output—for wood pellet producers.

How do we know that North Carolina’s forests are not being permanently destroyed?

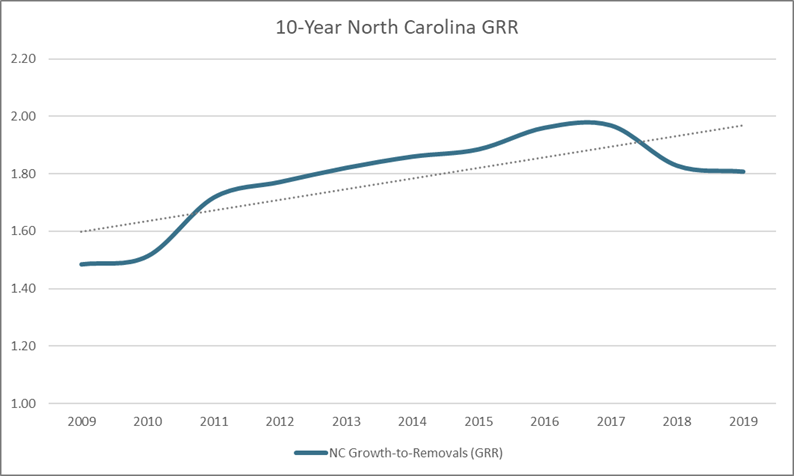

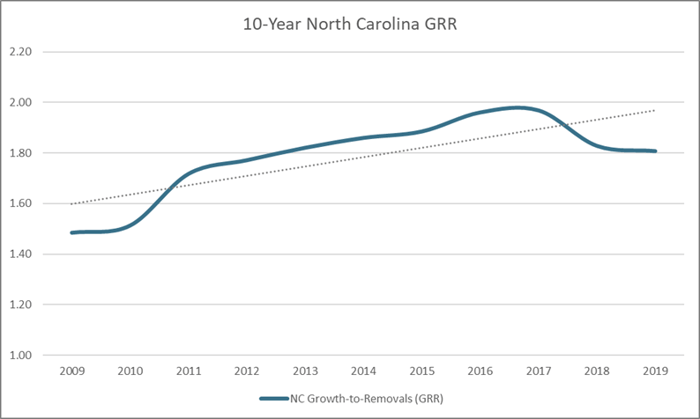

The most precise method to gauge the balance of tree growth and removals is to analyze the growth-to-removal ratio (GRR), which reflects the interplay between these two metrics in a given area. As an indicator of the trajectory of available supply over time (not a snapshot of availability at a moment in time), a GRR calculation quantifies overall forest sustainability.

A value of 1.0 suggests growth and removals are in balance; a value greater than 1.0 means forest inventory growth is outpacing removals (greater sustainability), and a value lower than 1.0 means removals are outpacing growth (lower sustainability). For example, a GRR of 1.33 means that growth is outpacing removals by 33%, whereas a GRR of 0.95 means that removals are outpacing growth by 5%. Adjusting for land-use changes, studies have shown GRR in a region tends to be cyclical over long periods of time as market forces react to high or low ratios that then move back toward equilibrium.

For the 10-year period from 2009-2019 (2019 includes the most recent data), North Carolina’s average GRR was 1.78, which means tree growth outpaced removals by 78%. Therefore, NC’s forests have an excess of available supply to accommodate the needs of its regional forest products industry, including wood pellet facilities.

Source: Forest2Market, Inc. (USDA Forest Service Data)

What about the specific counties mentioned in the articles above (Robeson and Northampton)?

- Robeson County: GRR is 2.74, which means timberland owners are growing 174% more timber volume than is being removed annually.

- Northampton County: GRR is 2.52, which means timberland owners are growing 152% more timber volume than is being removed annually.

This supply/demand dynamic is not unique to North Carolina; GRR throughout the entire US South is 1.79, which means timberland owners are growing nearly 80% more timber volume than is being removed annually. Industrial pellet exports represent a very small part of forest removals (and inventory) throughout the entire US South—roughly 5% of total harvests and 0.1% of total forest inventory.

As we continue to caution, any decrease in demand for forest products throughout the South could skew the balance between its timber markets and forest resources. In fact, an ongoing trend in this direction could put the region’s forest resources at risk of being underutilized as the growth of forest inventory continues to significantly outpace removals. When forest resources become chronically underutilized, land use changes can be an attractive alternative, and with such conversions, the forest will likely be lost forever.

When it comes to the issue of managing forests, environmental and economic concerns can often seem irreconcilable. Those unfamiliar with forestry and silviculture practices oftentimes approach this subject believing that there is either one advantage or the other, but not both. This is a common misconception parroted by many media outlets, and it simply isn’t true.

How do we know that a market-based system enables economic and environmental interests to work together?

An increase in forest stocking levels is the ultimate environmental benefit, which naturally occurs when landowners manage their timber resources for economic purposes. In the next installment on this issue, I will examine the data surrounding this symbiotic relationship, and demonstrate that new markets for wood products are imperative for keeping forestlands forested throughout the South.

Larry Sullivan

Larry Sullivan