4 min read

The Relationship between Demand and Forest Productivity in the US South: Part IV

Hannah Jefferies : August 8, 2017

This is the fourth in a series of posts covering the recently-published report compiled by Forest2Market titled “Historical Perspective on the Relationship between Demand and Forest Productivity in the US South.” Our analysis uncovered seven key findings related to the relationship between demand and forest productivity, which will be explored in this series. This independent report was commissioned by Drax Group, plc, the National Alliance of Forest Owners and the US Endowment for Forestry & Communities, Inc.

Other posts in this series: Part 1 Part 2 Part 3

Since the middle of the twentieth century, the amount of timberland—unreserved, productive forest land—in the US South has remained stable, increasing by about 3 percent between 1953 and 2015. During this period, economic growth and increased construction spurred consumer demand for forest products, which led timber harvests (or removals) to increase 57 percent. Yet over this same period, the amount of wood fiber (or inventory) stored in Southern forests increased 108 percent.

Forest2Market’s in-depth analysis of historical data over the past six decades documents the link between increased demand and increased inventory. Further, it explains that the dramatic increase in forest inventory was made possible by even more remarkable increases in productivity, especially on privately-owned timberlands. Encouraged by strong demand from the forest products industry, landowners made the long-term investments that were necessary to significantly improve forest productivity and increase inventory on a stable land base.

Key Finding #5

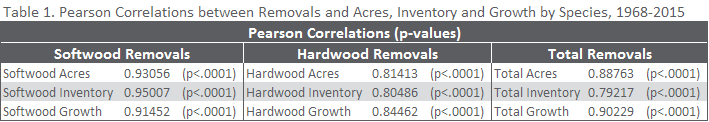

- The evidence is clear: Increases in removals are associated with more timberland acres, better growth and larger inventories. Analyses of privately-owned timberland in Southern states show that the observed historical relationships between Southwide demand and productivity are statistically significant. Removals have strong, statistically significant, positive correlations with acres, inventory and growth, especially for softwood species (Table 1). Models that use removals to predict acres, inventory and growth are also statistically significant and explain between 65 and 90 percent of the variance in acres, inventory and growth (Figure 2).

Removals vs. Acres

Removals are strongly and significantly positively correlated with timberland acres on a same-species basis (r=0.93 for softwood and r=0.81 for hardwood). Private softwood removals describe approximately 87 percent of the variance in private softwood acres. Hardwood removals explain less of the variance (66 percent) in hardwood acres.

Removals vs. Inventory

The strong, significant, positive correlations between removals and inventory are even stronger than those observed between removals and acres for softwood species: Softwood removals have an almost perfect positive correlation (r=.95) with softwood inventory. Private softwood removals describe approximately 90 percent of the variance in private softwood inventory. While somewhat smaller, hardwood removals still have a strong positive correlation (r=.80) with hardwood inventory. Hardwood removals explain approximately 65 percent of the variance in hardwood inventory, less than the variance in softwood inventory explained by softwood removals.

Removals vs. Growth

Removals are strongly and significantly positively correlated with growth on a same-species basis (r=0.91 for softwood and r=0.84 for hardwood). Private softwood removals explain approximately 84 percent of the variance in softwood growth. Hardwood removals explain a lower percentage of the variance (71 percent) in hardwood growth.

Summary

There are several reasons why softwood removals bear a stronger relationship to acres, growth and inventory. First, plantations, which largely occur on softwood stands, typically are managed to maximize output to produce a steady supply of wood and/or to promote predictable financial returns; other objectives, such as recreation and wildlife habitat may be secondary. Plantation stands require more upfront financial investment (i.e., stand preparation, planting and upkeep costs), but they are also associated with high growth and more regular harvesting, as we showed in Part 3. Second, softwood species also have shorter harvest rotations than hardwood species. Third, hardwood stands, especially those owned by non-industrial private landowners, may be managed with more diverse management objectives, and timber output may not be the landowner’s primary goal.

Key Finding #6

- Case study evidence confirms that increased removals are associated with increased inventory not only at a regional scale, but also in local wood basins. Further, they demonstrate that the markets in local wood basins are defined not by changes in demand from a single mill, but rather market-wide shifts in the demand for all wood products. In particular, shifts in demand for larger and more valuable sawtimber had a greater impact on case study forests and markets than did changes in demand associated with individual pulpwood-consuming mills. However, the case studies also show that when these basins had an active, centrally-located pulpwood-consuming mill, plantation acres increased more quickly, which helped retain total timberland acres in the face of declining naturally-regenerated timberlands.

Case studies of wood basins surrounding the Flint River, Georgia and St. Joe, Florida areas from the 1970s to 2015 show that these local wood basins tended to follow larger Southwide trends despite the fact that Flint River experienced the opening (in 1981) and St. Joe experienced the closing (in 1998) of a pulpwood-consuming mill. In both areas, removals, growth and inventory associated with both sawtimber and pulpwood increased over the study period (Figure 3, A-D). These localized findings are consistent with Southwide historical trends and statistical results linking increased removals to increased inventory.

In both basins, inventory, growth and removals were driven not by a single pulpwood-consuming mill; rather, they were shaped by regional trends and the actions of all local market participants, especially sawtimber consumers.

- First, the case studies failed to demonstrate that the opening or closing of a single-pulpwood consuming mill had the power to interrupt or reverse trends in pulpwood removals in these local markets. In both basins, trends of increasing pulpwood removals, which existed prior to the pulpwood-consuming mill opening (in Flint River, Figure 3-C) or closing (in St. Joe, Figure 3-D), continued after these mill events because other consumers were active in these basins.

- Second, because sawtimber-sized trees represented the majority of removals and inventory in both basins (compare Figure 3-A vs. Figure 3-C, Figure 3-B vs. Figure 3-D) and because sawtimber has historically been a higher-value product as shown by Forest2Market’s TOMG stumpage prices in Figure 4, shifts in sawtimber demand had the power to produce greater impacts on local forests than did changes in pulpwood demand. For example, in both basins, increasing sawtimber demand in the 1980s was followed by an expansion in plantation acres, which led to dramatically increased growth and inventory, first in smaller-diameter pulpwood) and later in larger-diameter sawtimber trees (Figure 3). Further, the Flint River case study supports previous Forest2Market findings that reduced sawtimber demand associated with the Great Recession caused landowners to defer final harvests until sawtimber market conditions improve, which limited pulpwood regeneration and inventory.

As in the US South (see Part 3), naturally-regenerated acres declined in both basins while plantation acres increased (Figure 3-E and 3-F). However, the case studies suggest when basins have an active, centrally-located pulpwood-consuming mill, plantation acres increase more rapidly, which helps to retain total timberland acres: In both basins, plantation acres increased more quickly when the central mill was active, which allowed total timberland acres to increase at a faster rate (in Flint River) and decrease more slowly (in St. Joe) (Figure 5).

For more detailed information and further reading:

At a Glance (report highlights)