4 min read

The Relationship between Demand and Forest Productivity in the US South: Part V

Hannah Jefferies : August 15, 2017

This is the fifth in a series of posts covering the recently-published report compiled by Forest2Market titled “Historical Perspective on the Relationship between Demand and Forest Productivity in the US South.” Our analysis uncovered seven key findings related to the relationship between demand and forest productivity, which will be explored in this series. This independent report was commissioned by Drax Group, plc, the National Alliance of Forest Owners and the US Endowment for Forestry & Communities, Inc.

Other posts in this series: Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 Part 4

Since the middle of the twentieth century, the amount of timberland—unreserved, productive forest land—in the US South has remained stable, increasing by about 3 percent between 1953 and 2015. During this period, economic growth and increased construction spurred consumer demand for forest products, which led timber harvests—or removals—to increase 57 percent. Yet over this same period, the amount of wood fiber—or inventory—stored in Southern forests increased 108 percent.

Forest2Market’s in-depth analysis of historical data over the past six decades documents the link between increased demand and increased inventory. Further, it explains that the dramatic increase in forest inventory was made possible by even more remarkable increases in productivity, especially on privately-owned timberlands. Encouraged by strong demand from the forest products industry, landowners made the long-term investments that were necessary to significantly improve forest productivity and increase inventory on a stable land base.

Key Finding #7

- Today, the biggest threat to forests is urbanization, but this threat can be mitigated by healthy markets for forest products, especially for products from highly-productive plantations. Nationwide, between 1982 and 2012, development was responsible for almost half (49.2 percent or 17.7 million acres) of all forest land that converted to other land uses. Conversely, forests reclaimed very little land (1.2 percent or 0.5 million acres) from developed areas. In the US South, the most productive plantation stands are best protected against conversion.

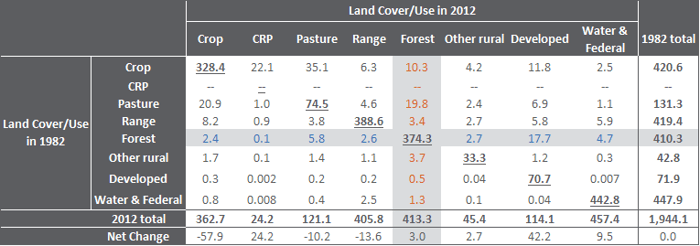

Nationally, overall forest land acreage increased 0.7 percent while developed land acreage increased 58.7 percent (Table 1). Across the United States, approximately 39.1 million acres were converted to forests from other uses. At the same time, however, 36.0 million acres of forest land were lost to other uses.

- Most of the acres that were converted to forest land were previously pastureland (19.8 million acres, 50.8 percent), cropland (10.3 million, 26.4 percent) or other rural land (3.7 million, 9.5 percent). Only 1.2 percent (0.5 million acres) was previously developed land. Rarely does developed land become forest.

- Of the forest land that was lost, most was converted to developed land (17.7 million acres, 49.2 percent), pastureland (5.8 million, 16.0 percent) or water areas or Federal land (4.7 million, 13.1 percent). These data show that over the past thirty years, the biggest threat to forests has been urbanization.

Table 1 Changes in Land Cover/Use between 1982 and 2012 - United States (million acres)[i]

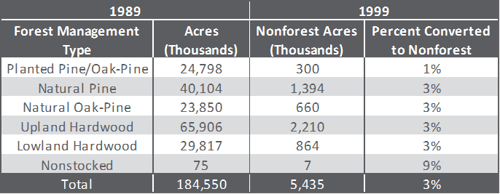

Between 1989 and 1999, 5.4 million acres of stocked timberlands in the US South were converted to nonforest uses (Table 2). Most (94 percent) were previously naturally-regenerated forest management types. Only 6 percent was previously planted pine/oak-pine.

Table 2 Timberland Acres Converted to Nonforest in 1999 by 1989 Forest Management Type

Conclusion

Our historical analysis demonstrates a strong relationship between demand, forest productivity and, ultimately, inventory. The rapid increases in inventory over the past 75 years coincided with consistent increases in forest products demand through the mid-2000s (see Part 1, Part 2). Productivity and output improvements were a result of the concerted efforts by the forest products industry to improve yield via improved tree genetics, silvicultural treatments and management practices (see Part 3). This is especially true for softwood species, which are often more actively managed. Government programs to promote reforestation and prevent soil erosion also contributed to the establishment and replanting of timber on non-industrial lands.

Our statistical analyses show clear links between removals and growth, removals and inventory and removals and acres (see Part 4). We argue that these attributes operate together to cause changes in forest inventories. Much as it was at the turn of the twentieth century when Southern forests had largely been cut-over, inventory—more specifically, the lack of inventory—can function to limit removals. High demand promotes investment in, and management of, timberland acres, improvements in growth and the building of timber inventories, as it did during the second half of the twentieth century. However, it is not possible to increase removals and maintain or build inventory unless growth and/or forested acres also increase. For the US South, increased growth is the link between increased demand and increased inventory because the forested area has remained stable. Foresight, planning and constructive action by the forest products industry and other private landowners were instrumental in ensuring that the South’s forest inventory continued to grow and remain sustainable as demand for forest products increased.

Since the 1950s, the South’s forests have demonstrated their ability to adapt to changes in demand without experiencing declines, and forest owners, who are predominantly private individuals, families, corporations and investors, have demonstrated their ability not only to use and maintain, but also to replenish and grow, the forest.

At the same time, forests face competing pressures, not least of which is urbanization as we discuss in a recent post. Looking to the future, one US Forest Service report forecasted the cumulative change in non-Federal forest land in the South through 2060 under four different scenarios. The scenarios differed in the degree of urbanization and the future value of timber, two important factors that will affect the future of forests. The results of the Forest Service analysis showed that the South was projected to lose between 7 to 13 percent of its forest land by 2060 (Figure 2).

However, the amount of forest land lost varied depending on the amount of urbanization and the changing future value of timber. The authors of the report wrote, “Between 30 million and 43 million [additional] acres of land in the South are forecasted to be developed into urban uses by 2060, from a base of 30 million acres [of urban land that existed] in 1997. The South is forecasted to lose between 11 million and 23 million acres (7 and 13 percent, respectively) of forests from 1997 to 2060. All subregions are expected to lose at least some acreage; nearly all of this area would be converted to urban uses. Strong timber markets can ameliorate forest losses somewhat, by shifting urbanization to agricultural lands.”

In the Forest Service analysis, higher urbanization and decreasing prices for timber resulted in the most forest land loss (Figure 2). Moderate urbanization and increasing prices for timber (D) resulted in the least forest land loss. Regardless of the degree of urbanization, increasing timber prices (B, D) functioned to mitigate, but not prevent, the loss of forest. In other words, increasing timber prices—which historically have been due to continued strong, healthy markets for timber—are key to keeping forests forested.

For more detailed information and further reading:

At a Glance (report highlights)

[i] For more information, see our recent post on land use change and urbanization.