3 min read

Wood Supply Chronicles, Part 2: The Unintended Consequences of Timberland Divestments

Pete Stewart

:

April 1, 2015

Pete Stewart

:

April 1, 2015

In the first part of this series, Wood Supply Chronicles, I highlighted three events that have changed wood supply in the US South: timberland divestment, the timing and intensity of the housing bust and inattention to—and an inability to react to—global policy changes.

In this post, I would like to focus more closely on the unintended consequences of timberland divestments from a perspective that few have considered and that might not seem apparent on the surface. It is, however, a viewpoint that is ultimately very important to maintaining the health of both individual forests and the larger forest products industry.

Demand from the forest is out of balance from an historical perspective. Why? Because demand for pine sawtimber has declined, while the demand for pine pulpwood has grown.

We all know why the demand for sawtimber has declined. What we cannot do, however, is predict its return or the scope of its growth when it does. The demand for pine pulpwood, on the other hand, increased significantly during this same time period. The result of these events is a tenuous market situation in which:

-

Pine pulpwood prices are high and pine sawtimber prices are low

-

An excess of pine sawtimber is available now and will be for years to come

The result is a forest that is simply out of balance.

My usual default position is that demand, regardless of the form, is a good thing. After all, demand provides the economic opportunity and incentives that landowners need to keep growing trees. But, at this particular time, are we considering the greater risk of becoming too one-dimensional from a products perspective? Is our shortsighted approach placing excessive risks on the entire system?

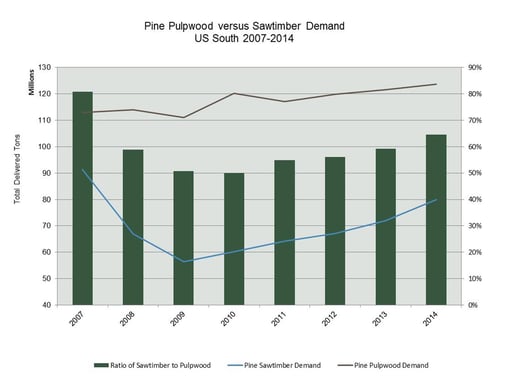

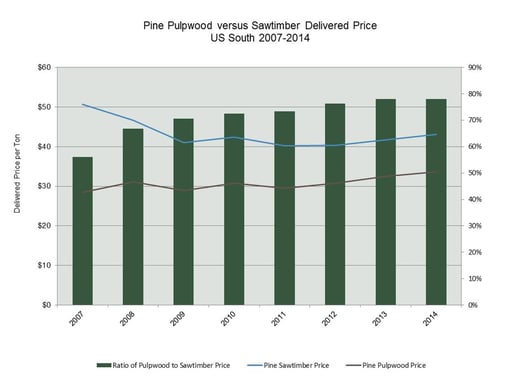

Take a look at the charts below and note the historical relationship between pine pulpwood consumption and pine sawtimber consumption, as well as the changes in price.

Over the past seven years, the relationships between pine pulpwood and pine sawtimber have been transposed and these historical connections are just beginning to level out.

In 2007, pine sawtimber demand was 80% that of pine pulpwood and by 2010, demand for pine sawtimber was about 50% that of pulpwood. As of the end of 2014, the demand for pine sawtimber has recovered to about 63%.

The result of this demand differential is manifested in price discrepancies between pine sawtimber and pine pulpwood. As you can see in Figure 2, delivered pine pulpwood in 2007 sold for roughly 55% of pine sawtimber. This gap has narrowed over the last several years, remaining stable at about 76%.

The reason that the price has not recovered with increased demand is that the low harvest levels over the past seven years have allowed for the accumulation of pine sawtimber inventory, and this has depressed prices.

You may be asking yourself, “Why does all of this matter?” Well, it does matter in the context of the southern pine plantation model. Consider the typical southern pine plantation that is growing at 7-8 tons per acre, per year. The harvest regime that typically maximizes net present value (NPV) of the forest and, as such, maximizes the economic return for the landowner goes like this:

-

A first thinning at about 15 years will produce roughly 40 tons of pulpwood.

-

A second thinning at 22-23 years will produce roughly 10 tons of pulpwood and 40 tons of small saw logs/chip-n-saw.

-

A final harvest at 27-28 years will produce roughly 90 tons of sawtimber and 15 tons of pulpwood.

-

Additionally, in the lumber manufacture process, roughly 25% of a sawlog will be chipped and ultimately used for making pulp.

Given the above data, we can assume that the typical pine plantation will yield between 95-100 tons of pulp fiber (including the chip conversion of sawlogs) and about the same volume of sawtimber material. So, an average pine plantation will yield roughly one ton of sawtimber for every one ton of pine pulpwood during its lifecycle.

This is the plantation regime that large commercial timberland owners favor because it has historically maximized their profits. Over the past seven years, however, the market has demanded substantially more pulpwood—almost twice as much as pine plantations have been growing.

This is where the unintended consequences of timberland divestment are most demonstrable. We are dealing with two dissimilar groups of owners with conflicting agendas: one group owns property and trees, the other owns mills. Timberland owners are trying to maximize their forest yields and profits by relying on past pricing norms and mill demands to set their harvest regimes. Not surprisingly, this data has historically been used in a very local context.

The mill owners, by contrast, are usually large multinational corporations operating numerous facilities. Not only are they maximizing profits across entire systems, but they are modifying mill outputs based on fluctuating consumer preferences. When the mills owned timberland, this data was quickly transferred back to the timberlands to close the information loop. This nimble operating structure and ability to rapidly respond to market demands has all but vanished, resulting in a gaping inefficiency in the supply chain.

Forest2Market believes that this knowledge gap will only expand as pulp mill owners continue to consolidate both nationally and internationally and as new consumers enter the market and the pace of changing consumer preferences increases. As this knowledge gap widens, supply chain inefficiencies will continue to intensify and the entire industry will suffer lower returns.