4 min read

Forest Carbon Markets Create New Opportunities for Multiple Stakeholders

Eric Kingsley

:

July 6, 2021

Understanding the complex relationships that exist between carbon emissions and environmental carbon sequestration is no small task. As ecological science goes, this is a relatively new field of study that is made more complex by the fact that the study area is global, and the time period is essentially infinite. Like all science, our understanding about this relationship continues to evolve.

However, the issue is now top-of-mind across the political and corporate landscapes as environmental, social and governance (ESG) initiatives are transitioning from vagaries just a few years ago to tangible, operational expectations. The investment community is increasingly applying these non-financial considerations as part of its analysis in identifying material risks and growth opportunities, and forest carbon markets are at the top of the list for several potential stakeholders.

As companies seek to address carbon emissions, there are emerging opportunities for forest landowners to be compensated for providing an important ecosystem service: the storage and accumulation of carbon on their woodlands.

Forest Carbon Sequestration 101

Forest ecosystems make up the largest terrestrial carbon sink on Earth. Trees draw carbon dioxide from the atmosphere through a process called photosynthesis, and every part of a tree - trunks, branches, leaves and roots (as well as the surrounding soil) - stores carbon. By weight, dried tree material is about 50% carbon. As part of the natural lifecycle, trees also release carbon dioxide back into the atmosphere when they decompose after death or burn during fires.

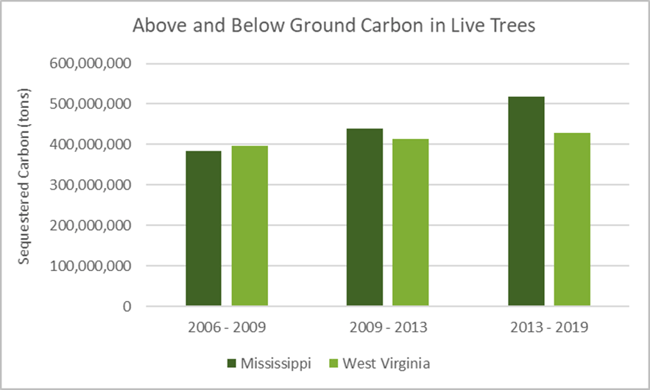

At a landscape level, the US Forest Service notes that the amount of carbon sequestered in forests closely mirrors the natural cycle of tree growth and mortality. At a more granular level, we can see the impacts of tree growth/inventory and carbon sequestration via two case studies from disparate forest types in two unique US states.

- The private working forests of West Virginia are primarily populated with species of mixed hardwood trees (oak, maple, etc.) that hold over 420 million tons of carbon – equivalent to the annual CO2 emissions of about 24 million gas-powered vehicles (for perspective, there are about 585,000 cars in WV).

- Conversely, the private working forests of Mississippi are primarily populated with species of mixed conifer trees (softwood pine) that hold nearly 520 million tons of carbon – equivalent to the annual CO2 emissions of about 30 million gas-powered vehicles (for perspective, there are about 850,000 cars in MS).

In both cases, sequestered carbon in live trees has increased over the last 15 years because forest inventory and growth have increased. In other words, the private forests in both states are growing more wood than is being removed for use in the forest products industry.

How are forest landowners benefiting from this increased tree growth — especially when the market value for their trees (stumpage) has largely been flat over the same time period?

Carbon Market Basics

Forest landowners are starting to see financial opportunities arise for the important work their forests perform in sequestering carbon. Markets are emerging that pay landowners to increase or retain carbon in their forests via continuous tree growth, paid by companies that either must (compliance) or want to (voluntary) offset their own carbon emissions.

While forest carbon markets are still young — most began developing at the beginning of this century — private forest landowners have been paid over $2.8 billion for carbon uptake and storage. There are now two major markets for forest carbon:

- A compliance market run through the California Air Resources Board, which requires commitments of 100 years.

- A voluntary market where companies elect to offset their carbon emissions, which requires commitments of 40 years using protocols developed by the American Carbon Registry.

Both markets require a detailed inventory of each registered forest to determine how much carbon is present, which is then used to model future forest growth and estimate how many credits (and how much money) can be generated by the forest. Due to the way most voluntary market transactions are structured, forest landowners are able to continue to harvest the annual growth of their ownership, which can be a few tons per acre per year.

It’s important to note that the forestland that participates in a carbon sale does not need to be contiguous. For landowners that have a long-term plan to harvest at or below the level of growth, this can make carbon projects a good fit with existing forest management plans and harvesting regimes.

Considerations for Landowners

It typically takes about 18 months from the start of a forest carbon project to the time when a landowner enters into a long-term contract and begins receiving revenue. After this, there are periodic inventory assessments to confirm carbon levels. For forests that will have ongoing timber harvests, certification is required via Tree Farm Systems, the Sustainable Forestry Initiative, or the Forest Stewardship Council.

It is not (yet) economically viable for all properties to pursue carbon registry; the costs of developing a project are roughly fixed regardless of tract size. Project developers struggle with any ownership that is smaller than roughly 2,500 acres (this can vary by geography – the key limits are really the volume of carbon in standing timber and the annual growth) and for other landowners, the restrictions are simply too burdensome to accept. However, for landowners with a long-term vision to grow and harvest sustainably, this may present an opportunity for additional revenue.

There are multiple ways to structure the voluntary 40-year commitments but very generally, landowners receive payment for standing inventory and are then free to harvest growth above that level. As noted above, for properties where the long-term strategy is to harvest only annual growth, this is an excellent opportunity for landowners to get paid for following their management plans. Landowners who plan to harvest below net growth over time can also receive payment in addition to standing inventory carbon.

Additional decision-making criteria for landowners include:

- Landowners can select what individual properties are included in their carbon registration deals, which provides flexibility for larger holdings depending upon future plans.

- As a rough rule, landowners need +/- 2,500 acres or more to make the economics of a carbon registration deal work. That said, there are opportunities for well-stocked holdings that may be somewhat smaller.

- In the event of a natural loss (fire, insect, disease outbreak, etc.) the participating landowner isn’t responsible for the loss, a small percentage of credits from every deal is added into an insurance pool to cover these circumstances.

- While there aren’t a lot of transactions to confirm this (since the carbon market is young), it is a reasonable assumption that an existing carbon deal will impact the sales price of registered timberland. Based on this, the most lucrative projects in the current market are those where landowners don’t plan on selling for the next 40 years. This is certainly the case for many family forests.

- Some landowners are choosing to use carbon registry as a form of temporary estate planning – basically entering a carbon deal now before handing land to a younger generation so they’ll be less inclined to sell (and will be older and maybe wiser when their options change).

For private timberland owners with property that might be a good fit for the voluntary carbon market, there’s no cost to get an assessment of what the opportunity might look like for your individual property. For owners who manage their forests in a way that cuts only growth (or adds inventory each year) and plan on holding the land for decades (or generations), this is a fantastic opportunity to get rewarded for carbon storage while maintaining regular forest management regimes.

Eric Kingsley is Vice President of Innovative Natural Resource Solutions, LLC. With a diverse professional background, Mr. Kingsley has been the Executive Director for a 1500 member forestry trade association, has represented organizations in both lobbying, legislative and development capacities, and has supported state and federal agencies with disaster relief funding for the forest industry.