There is growing sentiment that in order to combat climate change, we need more forest coverage to help absorb excess carbon dioxide (CO2). The “default” position of many NGOs and much of the public is that, to accomplish this goal, we should just let trees grow in perpetuity, and we should never cut them.

That’s not a good idea for a number of reasons but, more specifically related to climate change, it’s not the best way to maximize CO2 sequestration.

Per recently-published data by researchers at Western Sydney University (WSU) via their EucFACE (Eucalyptus Free Air CO2 Enrichment) study, there is new evidence that older trees in mature forests do not necessarily translate increased levels of CO2 absorption into additional plant growth and thus carbon sequestration.

Unique Research, Encouraging Results

While CO2 is the key ingredient in plant photosynthesis, experiments in which individual trees and young, fast-growing forests have been exposed to elevated levels of CO2 have shown these trees use the extra carbon to actually grow faster if they have the required supporting soil nutrients and water to grow. However, there has been some question as to whether mature forests would also be able to take advantage of the extra carbon and grow at the same rate since they also need nutrients from the soil to further develop.

In their unique experiment, which was applied to a mature native forest in Western Sydney’s Cumberland Plain, Western Sydney University researchers exposed a 90-year old eucalyptus forest to elevated levels of CO2. This particular forest grows in soils that are low in phosphorus, which is essential in combination with carbon to support optimal plant growth.

"Just as we expected, the trees took in about 12% more carbon under the enriched CO2 conditions," said Distinguished Professor Belinda Medlyn of the Hawkesbury Institute for the Environment. “However, the trees did not grow any faster, prompting the question 'where did the carbon go?’"

When the researchers dug deeper, their analysis showed something interesting occurring in their mature study forest: While the trees converted the absorbed carbon into sugars, they couldn’t utilize those extra sugars to increase growth due to the lack of sufficient soil nutrients. “Instead, they send the sugars below-ground where they 'feed’ soil microbes [fungi and bacteria],” explained Professor Medlyn.

This analysis also showed that once the carbon had cycled through the soil and was processed by microbes, it was then re-emitted into the atmosphere. Therefore, there is little to no carbon sequestration if 1) the soil conditions are poor, and 2) the capacity for significant growth of the tree is low, i.e. the tree is mature.

The study demonstrates that, when controlling for soil quality and nutrient availability, young trees have a greater capacity to utilize excess CO2, which encourages faster growth and an increase in carbon sequestration.

What Are the Long-Term Implications?

Most opponents of forest utilization (even for carbon-neutral biomass energy) have an incorrect view that timberland is a pristine, untouched reserve in a static state. i.e., large trees store lots of carbon in perpetuity (they never die and decompose). Nothing could be further from the truth.

With modern technology, it’s possible to harvest timber in a sustainable manner that also protects the many benefits we’ve come to expect from our forests. Sustainable management of our forests includes replanting after harvests, selective harvesting, protection of water sources and wildlife habitat, and wildfire prevention.

An unmanaged forest is an unhealthy forest, as well as a potentially dangerous tinderbox of wildfire fuel.

As one of many silvicultural practices, thinning allows for the continued growth of the healthiest species within a timber stand while removing the suppressed, diseased and low-vigor trees that will impede the growth of the entire stand, and serve as unnecessary fuel load during a major fire event.

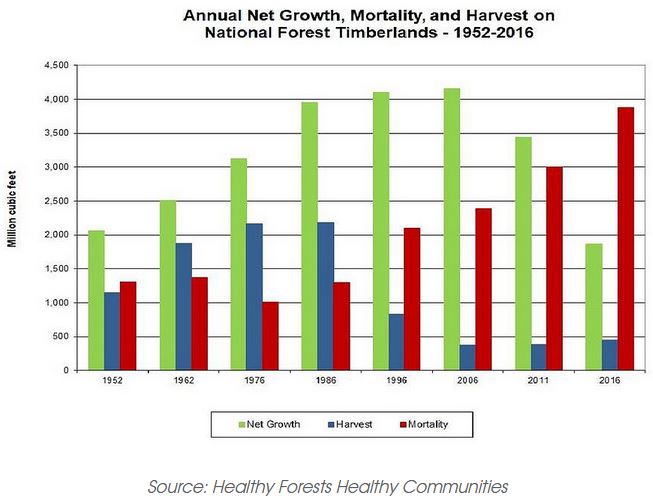

Per a 2017 Resources Planning Act (RPA) Assessment update to the Forest Resources of the United States technical document (the most recent available), the situation in public, government-managed forests in the western US is dire. The U.S. Forest Service (USFS) notes that forest mortality exceeded net growth on America’s national forest timberlands in 2016, creating a real risk for catastrophic wildfire.

Forest growth was 48 percent of mortality, while timber harvests were a mere 11 percent of what is dying annually—and this trend is on the rise. The agency estimates that 6.3 billion dead trees were standing in 11 Western states in 2015, up from 5.8 billion in 2010.

Myriad Benefits of Timberland

Forest utilization and the manufacture of wood products actually support our society and environment in many beneficial ways: housing/building products, paper products, energy, textiles, chemicals, and a myriad of other important products are derived from wood, which is one of our most valuable renewable resources. Long-lived products such as housing and building materials also sequester carbon for decades.

Sustainable forest management regimes have numerous ecological and economic benefits as well. Timber, and the land the timber is on, are economic assets. As is the case with any commodity product, when there is a healthy market for their assets, owners actively manage these assets to maximize economic return.

The private forest management system that is so prevalent throughout many regions of the US is a great example of how markets can work to help address environmental concerns. Trees are planted, grown, harvested and utilized—all while storing CO2—before the process begins again. As the WSU study suggests, these same techniques also help mitigate the risks associated with climate change.

The researchers at Western Sydney University add: “These findings have global implications: models used to project future climate change, and impacts of climate change on plants and ecosystems, currently assume that mature forests will continue to absorb carbon over and above their current levels, acting as carbon sinks. The findings from EucFACE suggest that those sinks may in actual fact be weaker or absent for forests on low-nutrient soils.”

In other words, the most effective way to maximize CO2 sequestration is to sustainably harvest mature trees for conversion into long-lived wood products such as lumber and furniture, and replant the harvested acres with new, young trees that will benefit from accelerated growth and carbon storage. This has been the approach of the forest products industry for years and, due to its imparted climate benefits, should be standard procedure going forward. If we really want to maximize CO2 sequestration in our forests—the most advanced carbon-capture devices in the world— we need to keep harvesting, utilizing, and planting more trees.

Stan Parton

Stan Parton